When Gov. Phil Murphy first discussed closing schools in March to slow the spread of a strange new threat called the “coronavirus,” he said it would be for an indefinite period of time.

Throughout the state, educators were plunged into crisis, as they transformed education for 1.4 million public school students from a classroom experience into a remote learning and internet experiment. In an interview, Newark superintendent Roger Leo´n remembered that during this time, everyone in his administration “worked like their hair was on fire.” He enlisted the help of the Newark media company, Audible, in printing 38,000 paper packets of lesson plans for the city’s students, enough for two weeks of learning. As the crisis mushroomed, Leon’s principals and staff roamed through the streets of the city in their cars late into the night, delivering 9,000 Chromebooks to students who needed them to gain access to the internet.

The crisis, however, would last much longer than two weeks, and the death toll was higher than anyone initially predicted. At the time Gov. Murphy signed his order to close all New Jersey schools on March 18, there were 178 New Jersey cases of COVID-19, the disease caused by the virus. Only two months later, on May 18, New Jersey officials were reporting 148,039 coronavirus cases and 10,435 deaths. New Jersey had the second-highest number of cases and deaths of any state in the nation. By then, the governor had ordered schools closed for the rest of the academic year. The rapid action of New Jersey officials likely saved many lives.

On April 16, even as the selectively lethal pandemic was still unfolding, the New Jersey School Boards Association announced it would release a report that would look forward to the issues and concerns that would confront educators, administrators and boards of education when and if schools can reopen safely. On May 20, that report, “Searching for a ‘New Normal’ in New Jersey’s Public Schools: An NJSBA Special Report on How the Coronavirus Is Changing Education in the Garden State,” was released.

During the month that preceded the report’s release, the NJSBA researched more than 100 articles, publications and studies, conducted interviews with school administrators, mental health experts and board of education members, and analyzed more than 1,000 responses to a survey issued to local school district leaders.

The schools must try to reopen, the interview subjects agreed. But they struggled to answer the serious questions about public health and the safety of the schoolchildren in their care. Among the issues: How much risk is acceptable? What safety measures are essential, and how can schools afford them? What would relieve financial pressure on schools? What conditions would establish a health emergency that would trigger schools to close again?

“In the two months since the COVID-19 pandemic forced the closure of our public schools, New Jersey’s education community has made a valiant effort to transition our students to digital learning,” said Dr. Lawrence S. Feinsod, NJSBA executive director. “Now, as we look toward the reopening of schools, the education community faces even greater challenges. Our report provides information on the safe reopening of schools, students’ mental health, academic and extracurricular programs, budgetary issues, and preparations for the future.”

10 Strategies and Recommendations

Based on interviews and research, the “Searching for a ‘New Normal’” report presents strategies for the consideration of local school districts and recommendations for action by state and federal governments. They are:

- Mental Health The mental health of students and staff is of the greatest importance. Before schools reopen, and before any evaluative tests are administered, school districts should make a sustained effort to establish a sense of calm and trust so that learning, and assessment of learning, can occur.

- Communication Administrators should engage in early, sustained communication with board members, parents and staff, outlining and thoroughly explaining the measures being taken so that they can instill confidence that schools will be a safe place. Before school reopens, all stakeholders should understand what the “new normal” will be, and how it will work.

- Protective Equipment Guidelines To sustain the health of students and staff, boards of education should work with their superintendents to adopt clear guidelines establishing the level of personal protective equipment (PPE) that will be provided by the district and what equipment may be brought from home. For example, will facemasks be required? What types of masks are acceptable? How will local PPE standards compare with guidelines from the state, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and other agencies?

- Emergency Action Plan Before schools reopen, boards of education should work with their superintendents to revise closing plans that address the resumption of full online instruction if school buildings are again closed due to health and safety considerations.

- Diagnostic ToolOnce a safe learning environment is re-established, academic assessment, that is appropriate to each district, should be administered to determine each students’ educational progress and to identify the need for remediation.

- Remedial Programs As early as possible in the budgeting process, the New Jersey Department of Education (NJDOE) should identify available funding for school districts to address the remedial needs of students.

- Flexibility The NJDOE should ensure that districts have the financial and regulatory flexibility they need to respond to the crisis. The New Jersey Quality Single Accountability Continuum (NJQSAC), which is the state’s monitoring and district self-evaluation system, should either be suspended or revised so that districts are not penalized for taking actions necessary to address the pandemic.

- Provide School Districts with Updated Financial Data To plan for the eventual reopening of schools, education leaders need accurate information now on the pandemic’s impact on revenue. Toward this goal, the state must provide local boards of education with updated information on funding for the 2020-2021 school year.

- A Menu of Options for Reopening In developing a blueprint to guide the reopening of schools, state education officials should work with stakeholder organizations and consider other states’ plans, such as Maryland’s Recovery Plan for Education, released May 6; and the Missouri School Boards Association plan, Pandemic Recovery Considerations: Re-Entry and Reopening, issued May 5. Both plans offer a variety of strategies and encourage districts to choose options that work best for their communities.

- Help Teacher Candidates Complete Training Schools were closed before teacher candidates could complete required classroom observations and training. New Jersey should formulate an appropriate plan to provide an adequate pool of teacher candidates for the upcoming year. Other states, including California and Maryland, have developed plans to help teacher candidates complete training.

Making Sure Students Are Ready to Learn Again

“I think the bigger question is how are we going to emotionally care for students who have lost three, four or five people in their family, because that is a reality for some of our kids…. Instruction is important, no doubt. But we also have children who are going through a very adult experience,” said Christina Dalla Palu, assistant superintendent, Dover Public Schools, Morris County.

Dover, a 2.5 square mile community had 647 coronavirus cases and 46 deaths by May 15.

In 2019, the NJSBA released a report on mental health services in schools, “Building a Foundation for Hope,” which found students in New Jersey and the nation “are in emotional trouble, with anxiety reaching near epidemic levels. As many as one in eight children, and 25% of teens, are contending with diagnosable anxiety disorders.”

Even before the coronavirus closed schools and disrupted the lives of students and families, the task force found that 2,731 young people, ages 10 to 24, were treated in hospital emergency rooms in New Jersey for attempted suicide or self-inflicted injuries in 2013 through 2015, the latest statistics available. Within the same age group, 283 suicides were reported.

The task force report included more than 70 recommendations about how school districts could work with mental health professionals and build alliances with their communities to address the emotional well-being of every child.

With the added stress of the pandemic and school closures, school districts may suffer a loss of a staff member or student. The Rutgers Traumatic Loss Coalitions for Youth offers free resources and assistance in the event of such an event. Assistance can range from phone consultation and support to the provision of on-site services. Each county has a coordinator; contact information is available.

Maureen Brogan, statewide coordinator of the Traumatic Loss Coalition, said it might take some time for students, especially younger students, to adapt to the “new normal” of potential restrictions. If students are required to wear masks in school, some may wonder why, she said.

“It may make younger children think, ‘Are we still not safe because we’re wearing masks?’” she said, adding that it may take some time before students and teachers stop reacting every time someone in the classroom coughs or sneezes.

The success of social distancing measures, she said, will rely on early communications with parents.

“Fear is fueled by uncertainty,” Brogan said. By involving parents, teachers and staff “early in the process,” school leaders can help their educational communities feel safe and secure, and no one will be surprised when school opens and new social distancing measures are put in place. Children take their cues from parents, she said, and if parents reassure them, children are more likely to accept what they’re required to do.

Questions Need Answers Even Before Academic Issues Can Be Addressed

- Before the uneven quality of online learning during the pandemic is assessed;

- Before agreement can be reached on suitable tests that will identify how far behind some children fell while schools were closed;

- Before remedial plans can be administered to restore students to their proper academic standing, important questions must be resolved before learning can begin again. Among them:

Who will drive students to school? A national bus driver shortage could be exacerbated by the need for more drivers to cover split sessions, if that is the option districts choose to address overcrowding. Even before the pandemic, in February, School Transportation News reported that 80% of school bus companies and school districts surveyed were having trouble finding enough drivers. In New Jersey, the minimum time to obtain a license is 34 days, provided that the process, including criminal history record checks and other requirements, goes well. If split sessions require the rapid-fire hire of more drivers, consider this: It can take months of often-unpaid training for drivers to earn a Commercial Driver’s License (CDL), according to School Transportation News.

Who will meet the increased demand to monitor students’ health? If teachers, parents and staff are to be convinced that classrooms are safe, who will monitor students’ health when there is one nurse available for every 533 students in New Jersey – and many of them are already busy monitoring medications students were routinely taking before the crisis. If students will need their health symptoms monitored, and their temperatures taken, who will do the monitoring and record the results?

Will there be enough teachers to staff the classrooms? Assuming students can get to school and their health is appropriately monitored, who will teach the classes? U.S. News & World Report, in a May 8 story, said that one-third of the teachers in the nation are over 50 years old. Will teachers and staff be convinced that it is safe to return to work, or will waves of retirements and sick days diminish the workforce at the same time that more teachers are needed?

West Windsor-Plainsboro Superintendent David Aderhold, who also serves as president of the Garden State Coalition of Schools, says he and his fellow superintendents do not have the answers, but they have “hundreds of questions” about how to move forward. Aderhold is a member of the state Senate Education Recovery Task Force, led by Sen. M. Teresa Ruiz, chair of the Senate Education Committee. NJSBA is also represented on the task force.

The task force will address a variety of topics, including overcoming the digital divide, mitigating learning loss, offering resources to improve at-home special education instruction and providing assistance for students who have Individualized Education Programs (IEPs) or are English Language Learners.

“What is ultimately going to drive our response is public health,” Aderhold said. “What’s in front of us is a pandemic global health crisis. What’s the appropriate role for schools in that?”

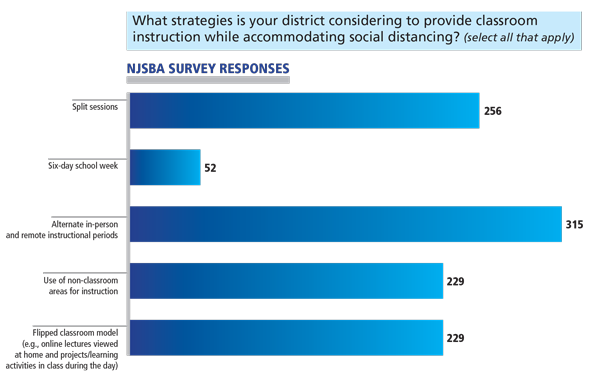

An NJSBA survey sent to school board members, superintendents, and school business administrators on April 16 drew more than 1,000 responses to the question, “What strategies is your district considering to provide classroom instruction while accommodating social distancing?”

An NJSBA survey sent to school board members, superintendents, and school business administrators on April 16 drew more than 1,000 responses to the question, “What strategies is your district considering to provide classroom instruction while accommodating social distancing?”

Nearly three out of ten respondents (29.14%) cited alternate in-person and remote instruction.

Another 23.68% favored split sessions. How, Aderhold asked, would that work?

“If you run split sessions, you’d have to double or triple your bus costs,” he said. His school district serves about 9,500 students in Mercer and Middlesex counties. With the state facing estimated budget shortfalls of $20 billion to $30 billion, where will the additional money come from?

“We don’t have the financial capability to expand our teaching sessions, so if anyone suggests that we can extend the day or have more sessions, I just say, financially, ‘How?’ And if you want to think in terms of eight-year-olds or 10-year-olds at a bus stop, there’s no such thing as ‘socially distancing’ them for long,” Aderhold said.

Layoffs of Historic Proportions? Gov. Murphy is predicting layoffs of “historic” proportions unless Congress approves more federal aid for states and schools, and unless Trenton legislators approve his plan to borrow billions, despite questions about whether such borrowing violates provisions of the state’s constitution.

On May 13, state Treasurer Elizabeth Muoio predicted a $2.8 billion revenue loss for the current fiscal year and a $7.3 billion shortfall in 2021.

“These revenue projections are based upon a wide variety of economic assumptions, including the assumption that there will not be a resurgence of COVID-19 cases later this year,” Muoio said in a statement. The governor’s recent public comments have painted a consistently grim picture.

“The fact of the matter is we are going to have serious cash flow challenges,” Murphy said on April 16, according to NJ.com. “Folks should assume we’re going to have to gut programs. And that will affect everybody in this entire state… If we want to both address our cash flow challenges as well as keep our best public schools in the country, keep our full ranks of public responders, all of that would be in jeopardy if we don’t find the capital.”

Key dates ahead:

Aug. 25:On or before this date, the governor is required to deliver a new state budget proposal, covering Oct. 1, 2020 through June 30, 2021.

Sept. 30: By law, the Legislature and governor are required to finalize the new state budget, covering that time period of Oct. 1 through June 30, 2021.

Preparing for the Future What if the virus returns in the fall or the winter? If schools reopen in September, administrators are already tasked with preparing to close again if health conditions warrant.

“We don’t have a single member who is not planning for some amount of distance learning next year,” said Mike Magee, the CEO of Chiefs for Change, a nonprofit network of district and state education leaders from across the country. “These things are impossible to predict, but it would be foolish not to have a system ready, if in fact you need to continue distance learning or if you have to return students to distance learning at some point next year.”

In Limbo: Fall Sports and Extracurricular Activities Fall sports and extracurricular activities are an important part of traditional school life. In an informal survey of football coaches and officials in New Jersey and around the nation, national CBSSports.com writer Mitch Stephens asked if football and other high school sports would be played in the fall.

“If social distancing rules still apply in the fall,” Stephens wrote on May 8, “it’s hard to imagine fans will be allowed. If so, will there be a limit? Will cheerleaders, student body and band members be allowed? Without any or all, the pageantry and magic of the game will suffer.”

When it canceled high school sports in the spring, the New Jersey State Interscholastic Athletic Association said it would turn its attention to preparing for the fall season.

“We need to do everything in our power to salvage the fall sports season,” said Sen. Paul Sarlo, a Bergen County Democrat who also serves on the NJSIAA Executive Committee. “In my opinion, it’s too soon to try and pin down a start date (for fall sports), but I encourage the NJSIAA and the conferences around the state to begin conversations and formulation of plans for potential start dates, whether it’s July 15, Aug. 1, Aug. 15 or not at all. Those conversations should begin sooner rather than later.”

Special Education Successes and Challenges In New Jersey, those who work with the state’s population of about 200,000 special needs students say they are making great progress but acknowledge that it has been difficult to provide services to all students who need them.

Dr. Gerry Crisonino, director of special services for the Jersey City Public Schools, and a member of the NJSBA Special Education Committee, said services rapidly improved once the State Board approved the delivery of online services to special education students on April 1.

“Our teaching staff has been amazing,” said Dr. Crisonino during an interview with the NJSBA. “They’ve been able to implement this overnight. If in the fall this has to happen, I think we’re well-prepared.”

Dr. Crisonino, who is also a school board member in Berkeley Heights in Union County, said speech therapy has been delivered online to more than 1,000 special education students in Jersey City. Several years ago, the city worked with Verizon to extend online service to areas of the city that needed it, he said.

Though he has been inspired by the level of effort to create online programs for special needs students throughout the state, Dr. Crisonino acknowledged that challenges remain to be resolved. For example, it may be a difficult adjustment for some students with autism if they are required to wear facemasks to protect themselves and others from the virus.

“Students who have some form of autism may have sensory issues, and they may not want something on their face,” he said, adding that he is hopeful that parents will work with their children at home to help them become accustomed to wearing the masks, if necessary.

Meeting a Challenge of Unprecedented Magnitude Looking toward schools reopening, the challenges – academically, financially, socially, logistically – eclipse those involved in the school closings. But as evidenced in the NJSBA special report, they can be met with guidance and support from the state and federal governments, the commitment of local board of education members, superintendents and other district leaders, and the dedication of our educators and support staff.

The New Jersey School Boards Association believes that the best practices, experiences, and concerns emphasized in the report will have a strong and positive impact as our state develops a process to reopen its schools.

For updated information, visit the New Jersey School Boards Association’s COVID-19 Resource Center.